Melanoma of the skin (cutaneous melanoma) is a malignant tumor originating from melanocytes, the skin cells responsible for producing melanin. While primarily occurring in the skin, melanoma can also arise in the eyes, ears, meninges, gastrointestinal tract, and mucosal surfaces such as the oral, genital, nasal, and sinus membranes. Cutaneous melanoma accounts for over 90% of all melanomas and is commonly observed in white populations1.

The incidence of all skin cancers, including melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancers (NMSCs), has increased significantly in recent decades, outpacing many other cancers. This rise may partly reflect overdiagnosis due to more frequent skin screenings, biopsies, and the histopathological overcalling of melanocytic lesions that might otherwise remain benign2. Between 1982 and 2011, melanoma incidence rates doubled to quadrupled among individuals of European heritage3. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the overall melanoma incidence rate in the US between 2017 and 2021 was 21.8 per 100,000 people, with the highest rates among non-hispanic white males (34.9 per 100,000) and the lowest among black females (0.9 per 100,000)4.

The common subtypes of cutaneous melanoma include5:

- Superficial spreading melanoma (70%)

- Nodular melanoma (15–30%)

- Lentigo maligna melanoma (10–15%)

- Acral lentiginous melanoma (<5%)

Rare variants include amelanotic melanoma, spitzoid melanoma, desmoplastic melanoma, and pigment-synthesizing melanoma (also known as animal-type melanoma).

Melanoma staging, detailed in the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, Eighth Edition, provides a critical framework for diagnosis and prognosis. Simplified, the stages are as follows:

- Stage 0: Melanoma in situ, confined to the top layer of skin.

- Stage 1: Cancer localized to the skin without lymphatic or distant spread.

- Stage 2: Cancer remains confined to the skin but with higher risk features.

- Stage 3: Cancer has spread to regional lymph nodes.

- Stage 4: Metastatic melanoma, where cancer has spread to distant sites such as the brain, liver, or lungs.

Approximately 85–90% of melanomas are diagnosed at a localized stage, with 70% being superficial spreading melanomas. For localized melanoma, prognosis is excellent, with survival rates comparable to the general population. A SEER database study6 analyzing nearly 100,000 US patients found no significant difference in life expectancy between individuals with localized melanoma and the general population. However, metastatic melanoma presents a starkly different outlook due to its aggressive nature and historically poor survival rates.

Treatment

Melanoma treatment varies by stage. Stages 0–3 melanomas are primarily managed with surgery, while Stage 4 metastatic melanoma requires systemic therapies like immunotherapy, targeted therapy, chemotherapy, radiation, or combination of these therapies. Surgery is typically not used in Stage 4 metastatic disease, as systemic therapies are more effective in managing widespread disease.

Before 2011, chemotherapy was the primary systemic treatment, with dacarbazine being the only FDA-approved drug. However, since 2011, immunotherapy has revolutionized melanoma treatment, significantly improving survival rates. Melanoma was the first malignancy to benefit from immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), which target checkpoint proteins such as CTLA-4, PD-1, PD-L1, and LAG-3. These proteins, expressed on T-cells, are exploited by cancer cells to evade immune responses. ICIs restore the anti-tumor activity of T-cells, enabling a sustained immune response. The FDA-approved ICIs for melanoma include:

- Ipilimumab (CTLA-4 antagonist)

- Nivolumab and pembrolizumab (PD-1 antagonists)

- Atezolizumab (PD-L1 antagonist)

- Relatlimab-rmbw (LAG-3 antagonist, approved in 2022).

Another recent advancement is talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC or Imlygic®), an oncolytic virus therapy for advanced melanoma. T-VEC is a genetically modified herpes simplex virus designed to selectively infect and kill melanoma cells while stimulating both local and systemic immune responses.

Targeted therapy addresses the high prevalence of genetic mutations in melanoma, particularly in the BRAF, NRAS, and NF1 genes. By inhibiting these mutations, targeted therapies effectively halt tumor growth.

Prognosis & Survival

The prognosis for metastatic melanoma has improved dramatically with the introduction of immunotherapy and targeted therapy. A 2018 Canadian study7 observed significant differences in two-year survival rates depending on the treatment modality: 6–17% for chemotherapy, 24–26% for targeted therapy, and 60–62% for immunotherapy. Among ICIs, PD-1 antagonists (nivolumab and pembrolizumab) showed the greatest survival benefit, followed by CTLA-4 antagonists (ipilimumab).

A 2022 Danish study8 of 1,500 metastatic melanoma patients reported a 16% increase in 1-year survival and a 7% increase in five-year survival between 2009–2013 and 2014–2018, see figure 1, below, underscoring the transformative impact of modern treatments.

Figure 1: Metastatic Melanoma 1-year and 5-year net survival 1989-2018, Denmark

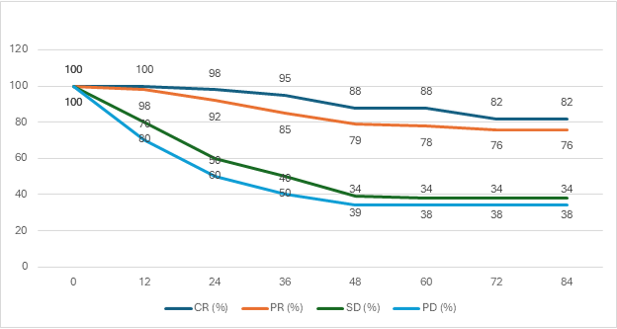

Recent studies9 have noted a fourfold improvement in median survival with immunotherapy, increasing from 18 months in 2018 to 72 months in 2022. Among patients achieving a complete response (no detectable disease at both the primary and metastatic sites), the five-year survival rate was 86-89% (see Figure 2 below). Approximately 70-75% of patients eligible for immunotherapy achieve a complete response.

Figure 2: Overall survival by best response in metastatic melanoma treated with combination of ipilimumab and nivolumab

OS = overall survival, CR = complete response, PR = partial response, SD = stable disease, PD = progressive disease.

Long-term benefits of immunotherapy persist even after treatment discontinuation. A 2021 study10 found that 73-76% of patients who discontinued immunotherapy after a median treatment duration of 15.2 months (range: 0.7-42 months) maintained a complete response, with four-year survival rates of 92–94%. For those achieving a partial response (no disease at primary location and stable disease at metastatic sites), four-year survival rates were 80–82%10 11.

When compared to targeted therapy, patients responding to immunotherapy have 1.5-fold better survival rates10.

Outlook

The outlook for metastatic melanoma continues to improve, driven by advancements in therapeutic strategies and ongoing research. Innovative approaches under exploration include combining multiple immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), integrating immunotherapy with targeted therapies, utilizing these treatments as neoadjuvant options, and extending the use of immunotherapy to non-metastatic melanoma to enhance survival outcomes further. Currently, more than 322 clinical trials in the United States are dedicated to advancing melanoma treatments options.

Dr. Rahul Nawander is Medical Director at Fasano Underwriting

Footnotes:

- Elder, David E., et al. “The 2018 World Health Organization classification of cutaneous, mucosal, and uveal melanoma: detailed analysis of nine distinct subtypes defined by their evolutionary pathway.” Archives of pathology & laboratory medicine 144.4 (2020): 500-522. Available at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32057276/

- Ref. Welch HG, Mazer BL, Adamson AS. The rapid rise in cutaneous melanoma diagnoses. N Engl J Med 2021 Available at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33406334/

- Whiteman, David C., Adele C. Green, and Catherine M. Olsen. “The growing burden of invasive melanoma: projections of incidence rates and numbers of new cases in six susceptible populations through 2031.” Journal of Investigative Dermatology 136.6 (2016): 1161-1171. Available at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26902923/

- Cancer Stat Facts: Melanoma of the Skin. Available at https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/melan.html Accessed on 12 Dec 2024

- Swetter MD et al, ‘Melanoma: Clinical features and diagnosis’ Available at https://www.uptodate.com/contents/melanoma-clinical-features-and-diagnosis Accessed on 12 Dec 2024

- Smith, Aiden J., Paul C. Lambert, and Mark J. Rutherford. “Understanding the impact of sex and stage differences on melanoma cancer patient survival: a SEER-based study.” British Journal of Cancer 124.3 (2021): 671-677. Available at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33144697/

- Hanna, T. P., et al. “A population-based study of survival impact of new targeted and immune-based therapies for metastatic or unresectable melanoma.” Clinical Oncology 30.10 (2018): 609-617.

- Luyendijk, Marianne, et al. “Changes in survival in de novo metastatic cancer in an era of new medicines.” JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute 115.6 (2023): 628-635.

- Wolchok, Jedd D., et al. “Long-term outcomes with nivolumab plus ipilimumab or nivolumab alone versus ipilimumab in patients with advanced melanoma.” Journal of Clinical Oncology 40.2 (2022): 127-137

- Kopecký, Jindřich, et al. “The outcome in patients with BRAF‐mutated metastatic melanoma treated with anti‐programmed death receptor‐1 monotherapy or targeted therapy in the real‐world setting.” Cancer Medicine 13.5 (2024): e6982

- Asher, Nethanel, et al. “Immunotherapy discontinuation in metastatic melanoma: lessons from real-life clinical experience.” Cancers 13.12 (2021): 3074.

Any views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and may not necessarily represent those of Life Risk News or its publisher, the European Life Settlement Association