The Institute and Faculty of Actuaries Continuous Mortality Investigation (CMI) published CMI_2023, its annual update to the CMI Mortality Projections Model in mid-April.

The bottom line is that projected life expectancies for those in England and Wales at age 65 are around five weeks lower for males and two weeks lower for females than they were in last year’s update.

On the surface, that may appear to be negative news, but taking a step back shows that standardised mortality rates generally in the two countries remain close to those observed in 2019, the lowest point in the last 40 years.

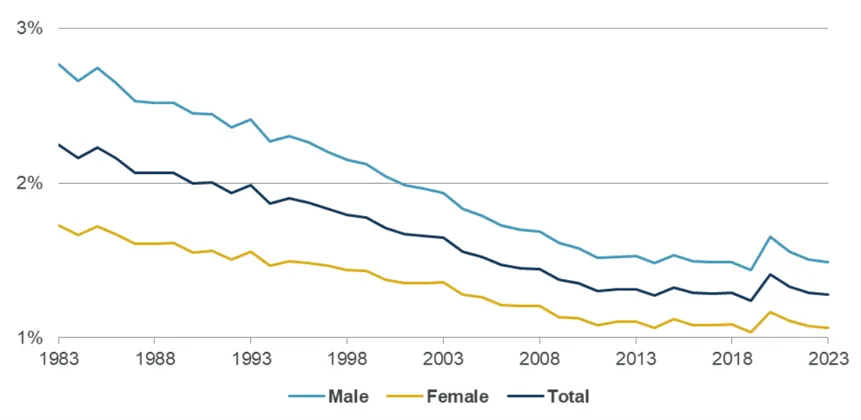

Figure 1: Standardised mortality rates in England & Wales since 1983

Source: Institute and Faculty of Actuaries

The biggest impact on mortality in recent years is, of course, the Covid-19 virus. As can be seen from the chart above, there was something of a spike in 2020 when the first wave swept through the population; despite the downward trajectory resuming, however, Cobus Daneel, Chair, CMI Mortality Projections Committee, says that the waters are still a tad muddy.

“While recent mortality has been similar to the period immediately before the pandemic, the outlook for mortality remains uncertain. It is unclear whether there are just lingering short-term effects of the pandemic that will rapidly fade or whether the pandemic will have a fundamental impact on the longer-term mortality trend,” he says.

The extraordinary impact of Covid-19 on mortality led the CMI to exclude 2020 and 2021 data from the most recent model, something that, anecdotally, many market participants agreed with. What is notable in the latest press release, however, is the reference to something of a conflict between insurer and reinsurer actuaries and pension consultants and other actuaries with regards to the weighting of the 2022 and 2023 data in this latest projection.

The former wanted 10%, the latter 25% or more. A cynic would argue that the dispersion is so wide because each side is trying to influence the CMI to their own ends. Insurers and reinsurers benefit from a lower weighting because it enables them to charge more for pension risk transfer deals, whether they be a full buy-out, a buy-in or a longevity swap because a higher life expectancy means a higher premium will need to be paid by the risk cedant.

On the flip side, pension trustees and actuaries want a higher weighting applied to 2022 and 2023 data because a lower life expectancy means a lower premium, thus benefitting the plan sponsors.

Ultimately, both sides met in the middle, with the CMI allocating a 15% weighting to these years.

“Our chosen weight of 15% strikes a balance between these views and leads to a modest fall in life expectancies compared to CMI_2022,” says Daneel.

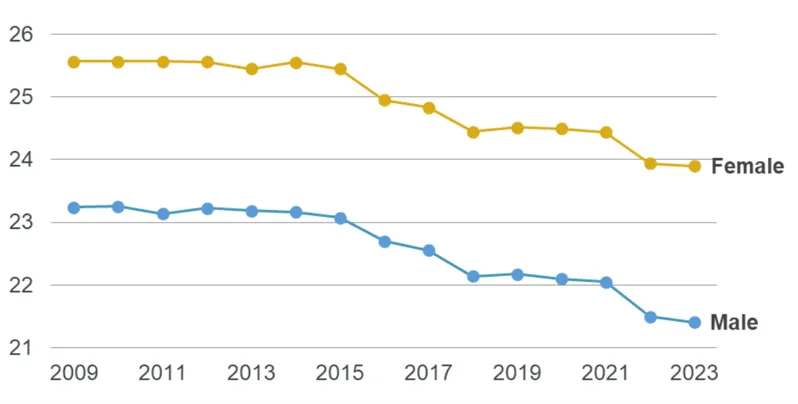

The end result is that the figures for CMI_2023 are around 21 months lower than in the first version, CMI_2009, for the age 65 cohort.

Figure 2: Cohort life expectancies as at 1 January 2024 at age 65 from CMI_2023 and earlier versions

Source: Institute and Faculty of Actuaries

Life expectancy varies in terms of members of different pension schemes, and these differences are considered in the pricing of pension risk transfer deals; no two PRT deals are the same. Still, Roger Lawrence, Managing Director at consultants WL Consulting, says that the latest information coming out of the CMI shows just how uncertain mortality is at the moment.

“The main issue here is still the long-term impact of Covid-19 and whether mortality in 2020 and 2021 was a one-off blip or whether it will have a more prolonged effect. The difference of opinion between groups for 2022 and 2023 data shows just how uncertain the outlook is generally for mortality, and therefore the success of these PRT deals.”