The UK government’s Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) maintains a Mortality Profile for England, a database which provides trends in mortality rates for a wide range of causes of death in England; the main update comes in November each year, when data for the prior year becomes available.

A recent update from May this year, however, brings together a selection of mortality indicators which the DHSC says is designed to ‘make it easier to assess outcomes across a range of causes of death’ in England.

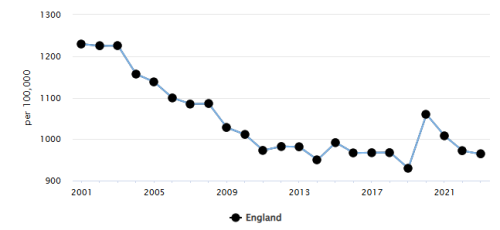

It is mostly good news for the general population; the mortality rate from all causes for all ages for both sexes fell in 2023 to 964 deaths per 100,000 people, the third lowest figure since 2001.

Figure 1: Mortality rate from all causes, all ages (Persons, 1 year range)

Source: Office for Health Improvement and Disparities, Department of Health and Social Care

The overall numbers mask a couple of noticeable trends for mortality rates for certain diseases, however.

The DHSC uses a categorisation system for the trends it produces; the all-cause mortality rate above is ‘decreasing and getting better’, for example.

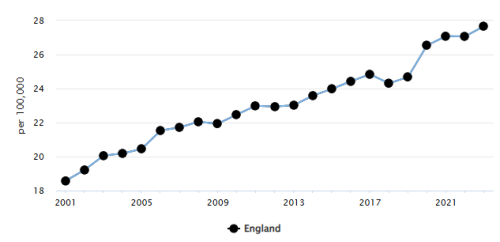

But for liver disease, mortality is ‘increasing and getting worse’. The mortality rate for those with liver disease has been on the rise for 25 years. In 2001, only 18.6 per 100,000 people died, a number that, at the end of 2023, stood at 27.7 per 100,000 for all persons, all ages.

A couple of factors are driving the trend.

“Together, alcohol, viral hepatitis, and overweight and obesity are the major causes of liver disease. Alcohol consumption patterns vary according to age, sex, and socioeconomic status; the pandemic amplified risky drinking behaviours in those already considered to be high-risk drinkers,” said Nicky Draper, Director of Life & Health Consulting at Crystallise.

“In addition, England has, like many other countries in the developed world, high rates of obesity and Type 2 diabetes in the population. Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD), which is generally brought on by poor diets, high in sugar and saturated fats, and sedentary lifestyles – can progress silently to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and eventually cirrhosis or liver failure, even in non-drinkers.”

Figure 2: Mortality rate from liver disease, all ages (Persons, 1 year range)

Source: Office for Health Improvement and Disparities, Department of Health and Social Care

Combating this rise is certainly on the radar of the public health overseers. The UK Health Security Agency published a call to action back in 2021 and then towards the end of that year, the EASL–Lancet Liver Commission called for ‘a paradigm shift in European Liver Disease response’.

Current initiatives, then, do not seem to be going far enough. It doesn’t help that most people don’t know they’re at risk until it’s too late — liver disease is largely symptomless until advanced – and there is something of a crowding out effect impacting efforts, too.

“Cancer, strokes, and heart disease, for example, receive significantly more funds and awareness than liver disease does. It is unfortunate and frustrating, because it’s such a preventable disease when compared to many others,” said Draper.

One trend where there has been a reversal in recent years is in the respiratory disease category. Similar to the trend in the general mortality rate, respiratory disease mortality has been trending downwards – until the past three years. In 2021, 93.8 deaths per 100,000 were observed, which, at the end of 2023, was 117.8; another one for the ‘increasing and getting worse’ bucket. However, the impact of the lockdowns could have a bearing on this trend.

“The rates appear to go down in 2020, no doubt due to the effects of social distancing and the subsequent reduction in flu, and other respiratory illnesses at the time,” said Draper.

There are areas where the mortality picture in England is better. Cancer, for example, has been on a downward mortality trend for the past 25 years, and despite a blip in 2022, continued its ‘decreasing & getting better’ trajectory in 2023. And while the trend for cardiovascular disease – which, at 232.4 deaths per 100,000 in 2023 – has been plateauing recently (largely due to adverse lifestyle behaviours being on the increase, and Covid-19, both primary as in direct damage to the cardiovascular system, and secondary, the delays in healthcare), the mortality rate is not increasing at this time.

The bigger picture to all of this is that mortality is getting harder to predict, not easier, and one reason could be the impact of Covid-19.

“Some of the trends in disease mortality in England, such as in liver disease, are very consistent trends – they are gradually and consistently improving, or gradually and consistently worsening, and modelling for that, for example, is unlikely to change too much unless the government puts significant sums into preventative measures that significantly stem or reverse the decline,” said Draper.

“But in instances where you see trend reversals, then of course, that’s more difficult to incorporate, even into general population models. Before the Covid-19 pandemic, there was more certainty with regards to the direction of travel for many diseases. But when you have such a disruptive situation like Covid caused by a virus that is able to have such a broad effect on many body systems, I think we’re still seeing the shake-out of the impact of that, to a degree.”