In this paper I will discuss mortality and life expectancy trends in the 20th and 21st centuries, developments that offer the potential to extend life expectancy, and funding constraints that may limit that potential.

20th Century:

US life expectancy (at birth) increased steadily in the 20th century, from 48.2 years in 1900 to 76.5 years in 2000.

– Mortality improvements in the first part of the 20th century were influenced by a reduction in childhood mortality and infectious diseases due to better sanitation and safer drinking water.

– Mid-century improvements resulted from further decline in infectious disease associated with widespread use of antibiotics and vaccines, with benefits spread evenly across ages.

– Late century improvements were associated with a reduction in cardiovascular mortality due to medical technology that resulted in better diagnostics (echocardiograms, cardiac MRIs, etc.) and treatments such as bypass surgery, cardiac angiography and the like, as well as blood pressure and cholesterol drugs. These improvements disproportionately benefited those over age 65.

21st Century:

Life expectancy continued to improve, in part due to reduced cancer mortality, from 76.5 years in 2000 to 78.9 years in 2015; but then we back tracked to a life expectancy of 76.4 years in 2022, leaving 21st century performance flat thus far. The recent decline in life expectancy was due primarily to COVID-19 related deaths, but also due to drug related accidental deaths. COVID-19 deaths are trending down now, with a significant impact on total US deaths.

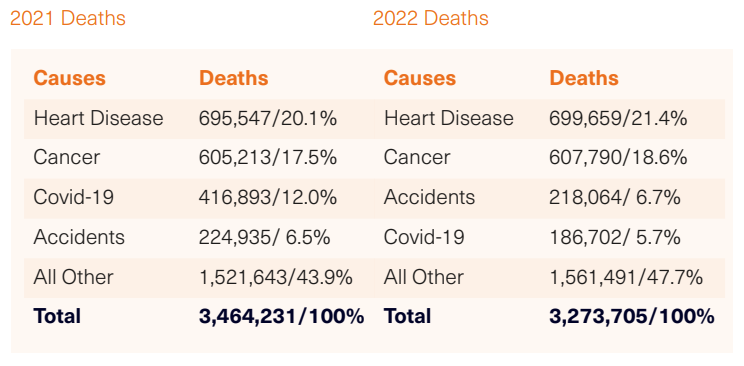

Provisional mortality data published by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) reveal a decline in total US deaths from 3,464,231 in 2021 to 3,273,705 in 2022, a reduction of 190,526, or 5.5%. This drop correlates strongly with the decline in COVID-19 related deaths from 462,193 in 2021 to 244,986 in 2022, a reduction of 217,207. Details on the four major causes of death are as follows:

Predicting the future is always dicey, but I think it is reasonable to assume some further reduction in COVID-19 mortality and, hopefully, drug related deaths as well. If so, an increase in U.S. life expectancy of up to two years in the next 3 to 5 years would be possible. The question is whether we have the potential to increase life expectancy beyond that.

Potential Future Improvements:

– There remains significant potential for continued improvement in cancer mortality through nano cytology-driven early detection, genetic profiling, and targeted therapies that attack increased signalling for cell growth, evasion of cell death and increased blood vessel formation associated with cancer growth. Eliminating all cancer deaths would add three to four years to life expectancy at birth – theoretically possible, but I think unlikely in our lifetimes. If we achieved half of this potential, life expectancy could possibly increase by 1.5 to two years.

– Regenerative medicine offers potential, including

(a) miniaturized, implantable and wearable devices that can alter electrical signals to stimulate nerve regeneration,

(b) injectable biomaterials that can trigger desired cell responses, and

(c) organ/tissue transplants.

Research suggests potential for spinal cord regeneration, as well as treatment of neurocognitive disorders like ALS and dementia, and possibly even cures for diseases like diabetes. While these developments offer clear potential for morbidity improvement, the longevity potential is likely to be gradual over a time and not as dramatic as treatments that would significantly impact cardiovascular or cancer death rates.

– Epigenetics; PAI-1 levels; diabetic medications: DNA methylation has identified plasma PAI-1 levels as a significant independent predictor of lifespan. A small cohort of an Indiana Amish community with a genetic mutation associated with lower PAI-1 levels lived about 10% longer than the rest. Medication to lower PAI-1 level is in trial phase now and could offer longevity benefits, as could medications reducing insulin resistance, such as Metformin.

– Biologic Age; Hayflick Limit: Biologic age remains in the range of 120 years and is the ultimate cap on longevity. The Hayflick Limit has shown that cells divide freely to a predetermined number of divisions and then enter senescence, which correlates with aging. Cancer cells produce an enzyme that preserves the telomere cap at the end of DNA strands and thereby allows unlimited cell division. Biologic age could theoretically be extended IF we could replicate the cancer enzyme in other cells, but this is not likely to happen in our lifetime.

– Ethnic Demographics: For a number of reasons, Hispanic life expectancy in the US is shorter than average, while Asian life expectancy is longer. The Hispanic percentage of population is projected to increase from 17.8% in 2016 to 27.5% in 2060, which will dampen LE extension, offset in part by an expected increase in Asian percentage from 5.7% to 9.1%.

Funding Constraints:

Ours is an aging population with the percentage of ≥ 65-year-olds is projected to increase from 15.2% of population in 2016 to 20.6% in 2030, while the percentage of 18 to 64-year-olds decreases from 62.0% to 58.1%. This will generate greater retirement and medical expenses with a smaller workforce to fund them. U.S. versus Russia and China tensions will keep defense spending at high levels. At the same time, with federal debt to GDP in the range of 120%, at Second World War levels, the debt service burden will be a significant drain on budgetary resources, while our borrowing potential will be constrained. The microchip revolution was the Industrial Revolution of our generation, but it has run much of its course, with no likely equivalent in the foreseeable future to generate substantial productivity increases. All things considered, it is hard to believe that there will be significant public funding available over the next decade for breakthrough longevity research to extend life expectancy.

Mike Fasano is Senior Underwriting Consultant at Fasano Associates

Footnotes:

1. Ahmad FB, Cisewski JA, Xu J. Anderson RN. Provisional Mortality Data – United States, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2023; 72:488-492. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr7218a3

2. CDC. National Center for Health Statistics

Any views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Life Risk News or its publisher, the European Life Settlement Association