I find it interesting to draw parallels between theories we see in the Life Expectancy space and what was considered state-of-the-art medical treatment throughout history. Procedures once considered vital have been studied and debunked as unsafe. For example: bloodletting, a medical procedure widely accepted by ancient Egyptians, Greeks, Romans, was still used in the 18th century. Bloodletting was performed on George Washington in December 1799, likely hastening his death. It persisted across centuries as an accepted medical practice despite its extremely harmful effects.

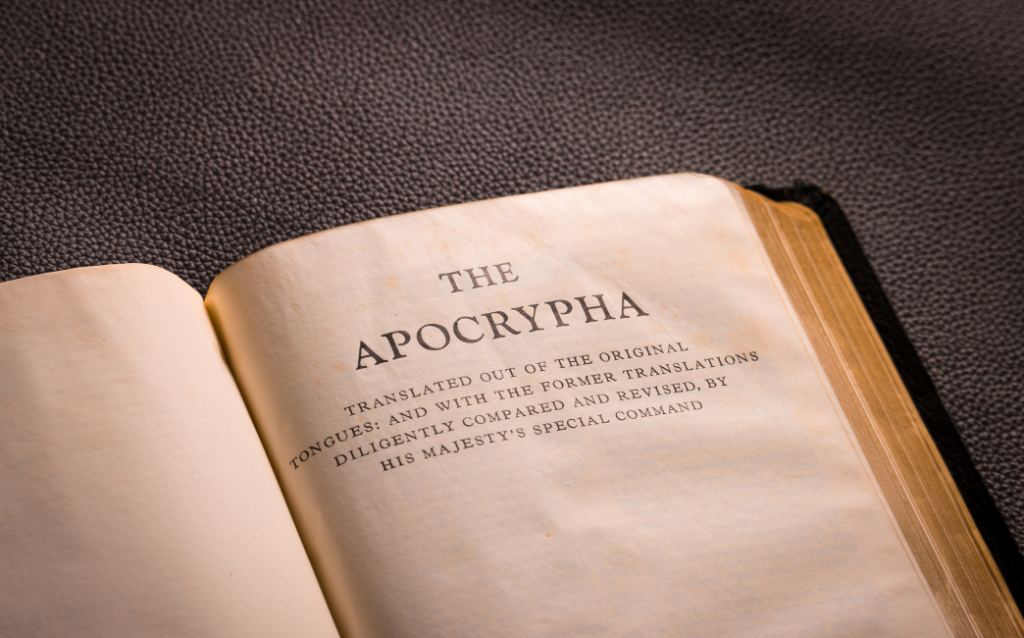

Similarly, certain misguided philosophies and theories have been proffered by life expectancy providers, and some are still being advanced today. Allow me to review some of these doctrines I consider to be apocryphal, that is, lacking authenticity and of questionable credibility. Many persist despite being disproven several times over.

First, let me summarize what I consider to be a solid data-driven process for determining a life expectancy estimate. In a perfect world, the base mortality table and underwriting manual are developed from analyzing life settlement lives. Our world is far from perfect, so some substitutions must be made. US Life Insurance data or US Population data may be considered, but with considerable judgment applied, recognizing that these populations differ greatly from the life settlement population.

For example, mortality improvement data for life settlement insureds is not statistically significant at this point; this means additional data must be considered, such as life insurance studies related to mortality trends. Consider heart disease, the biggest mortality threat 30 years ago, has more successful treatment options now and no longer carries the same risk. Cognitive and pulmonary issues, on the other hand, are becoming more toxic.

We hopefully can consider current medical records that range from at least 3 years ago to today. Underwriters identify relevant conditions by applying the manual consistently and the resulting mortality multiplier is applied to the base mortality table, calculating the life expectancy of someone selling their policy.

With the above ideal in mind, consider the following practices that may be common among industry participants, but are not valid:

- Averaging Two or More LEs. I must admit, I haven’t heard about this one in a while, but I know it still occurs. It is never proper to use the average of two or more LEs (e.g. use 75 as the average of an 80 month LE and a 70 month LE). If you want to use a combination of two or more different LEs, you should average their survival curves (not mortality curves, survival curves) and then calculate the combined LE from the averaged survival curve.

- Aging LEs. What is the proper way to utilize an LE that is not fresh; one that has been around for months or even years? First, recognize that the LE certificate date may not be the best point to begin. The date on the insured’s latest medical records is the true date they were evaluated. From that time on, one can assume that the insured will become less and less like the homogeneous group they were part of on the date of those records. One can reflect this to a certain degree by normalizing the survival curve (i.e., find the point on the curve that represents the time passed since the last medical record or the time since the certificate date, then divide every other point on the survival curve by that point, which creates a new survival curve).

Further judgment should be reflected to account for the insured’s current health. For example, in the case of a cancer diagnosis 2 years ago, there are definite differences between an insured in remission versus one who has had their cancer recur. - Mortality and Underwriting are Independent. In determining a life settlement life expectancy this is false. They are intertwined. Inextricably. The notion that one can separate these processes and mix or match them is misguided. To suggest that one or the other plays a larger role in determining life expectancy is folly, especially in the life settlement market, where the unimpaired lives (base table) do not resemble other populations and a large portion of the folks selling their policies have significant impairments (underwriting process) that must also be considered.

Let’s use a hypothetical example of two major underwriting companies: I will call one of them LEs-R-Us and the other, Acme LE. Assume LEs-R-Us has a light base mortality table and heavy underwriting debits relative to Acme LE, which has the opposite – heavy base mortality and lighter debits. Hypothetically, each company may weight their tables differently, but to be contextually correct, it would be foolish to mix LEs-R-Us table with Acme LE underwriting or vice-versa. Hypothetically speaking, folks would know that. - Proprietary Mortality Tables are Bad; the VBT are Good. Looking at the second part of this statement, the VBT – or Valuation Basic Tables – are built for the life insurance industry, using life insurance data. Further, as valuation tables, they have extra mortality built in, which is conservative for their designed purpose (life insurance valuations) but aggressive for life settlements.

At one time, life settlements’ folks thought the VBT were the best tables to illustrate life settlement mortality, but they were sadly mistaken. It was evident as far back as 2008 (when LEs were notoriously extended) that LE providers who based their tables on the VBT (virtually every LE provider in 2008) were generating LEs that were too short. When the latest VBT were introduced reflecting 2014 mortality, it was again proven that the VBT were inappropriate tables for life settlements. As for the assertion that proprietary mortality tables are bad, it really depends. The best data from which to derive life settlement mortality is life settlement data; pure and simple. If a proprietary table is properly and faithfully based on life settlement data, it is a good table; if not, it is not. - Back-Solving Into a Known Table is Acceptable. If you know the LE but do not know the table, it is problematic when pricing a policy. So inquiring minds decided to back-solve into a known table, such as the VBT, to solve this dilemma. The only problem is that it doesn’t work. Back-solving forces the shape of the known table onto the LE without regard for the accuracy of doing so. While it is worse to use the VBT as a base mortality table, back-solving an LE into the VBT is nearly as bad.

- Once an Impairment or Impairments are Identified, It is Easy to Determine When an Individual Will Die. This misguided principle suggests that there is no statistical fluctuation in human longevity, and nothing could be further from the truth. In fact, a healthy person can die tomorrow, while a highly impaired person can live beyond expectations. This statistical fluctuation may well be the reason for so much variability in LE estimates. Without significant and specific life settlement data, the range of potential outcomes is large. With human longevity, there is much more data available, but, as should be obvious to industry participants, the life settlement population is a very tiny subset of the total human population, and it does not behave like that larger population.

- Micro-Underwriting or Individual Underwriting is Necessary AND Sufficient. This theory is related to the concept that underwriting is primary in determining life expectancy. As discussed above, both the base table and the underwriting process are critical to determining life expectancy. Ignoring either is perilous. Sometimes emerging discussions within the industry postulate which discipline is most important in determining life expectancy – actuaries, underwriters, and more recently, data scientists. The disciplines do not matter – it is the discipline to rely on relevant data that matters. Data that reflects life settlement mortality for relatively healthy lives for the base tables, and data that reflects life settlement mortality deltas for the various impairments to inform the underwriting process.

- Underwriting is not Based on Data. This is more an inference than a philosophy, and it usually follows a statement about base mortality tables being reliant on lots of data. In truth, underwriting debits and credits are also dependent on data, or should be. Any nuances that are not statistically significant are an exception only because the data does not yet exist in sufficient quantities. This makes estimating life expectancy somewhat difficult.

For example, without data, one might think that high cholesterol shortens life expectancy; that’s good logic. Unfortunately, it is not correct, thanks to the ubiquity of statins. However, if evidence exists that suggests the insured cannot tolerate statins, that must be factored into the life expectancy as an exception.

As in bygone days with folks relying on apocryphal medical philosophies to their demise, relying on the above life settlement practices will likely lead to a bad result for industry players. Dr. Howard Markel, writing about George Washington’s medical team, opined, “The truth of the matter is that they did the best they could… …using now antiquated and discredited theories of medical practice.” Hopefully, we will not be similarly judged for using the above apocryphal life expectancy practices.

Vince Granieri is CEO at Predictive Resources

Any views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Life Risk News or its publisher, the European Life Settlement Association